Shipping is an important source of carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions but is a hard-to-abate sector. Reaching net zero in 2050 will require ECAs to help in the shipping industry’s green transition.

Large CO2 emissions

International shipping represents 3% of global CO2 emissions, equal to the whole of Germany. While shipping is not included in the Paris Agreement, the International Maritime Organisation (IMO), representing almost 90% of world tonnage, took on the challenge and made commitments in 2018 to halve emissions by 2050. Last year, the IMO committed to achieving net zero in or around 2050 and set a deadline to introduce measures and regulations in 2027.

The challenge of reducing emissions from deep-sea transport

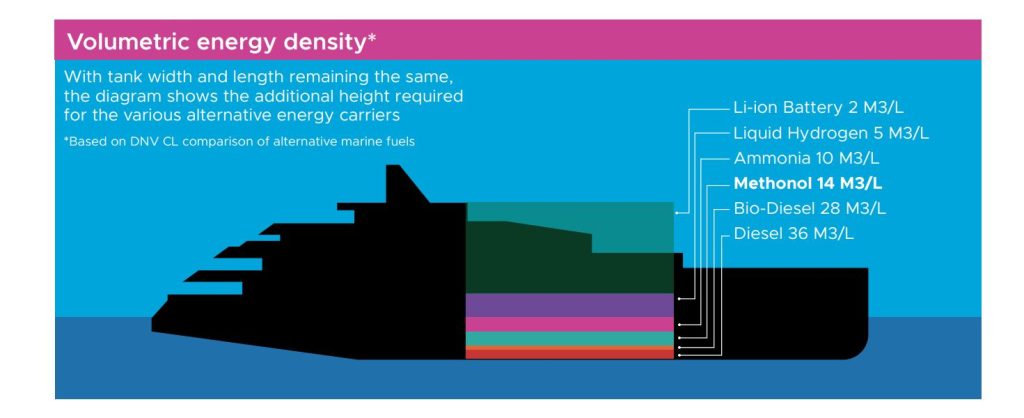

Long-distance shipping is a hard-to-abate industry for several reasons. Transport along the coast and on inland waterways is significantly easier to electrify, as shorter distances allow the necessary frequent charging of batteries. This is not the case in deep-sea transport, which represents the bulk of emissions. A major challenge for the maritime industry is the availability and cost of low-carbon fuels. Zero-emission fuels are several times more expensive to produce than fossil fuels, and shipping competes for these fuels with other transport sectors. Although more

space efficient than batteries, alternative fuels also require much more space on board than conventional fuel. Demand has yet to reach scale, and investment in production remains far below the levels needed to meet the IMO targets.

However, progress has been made. The IMO has had requirements regarding the energy efficiency of new transport vessels since 2013. New ships being built must obtain a certain level of energy efficiency (Energy Efficiency Design Index, EEDI). For certain ship types, container ships in particular, emissions have been reduced considerably since the introduction of this regulation. These reductions have largely been achieved through the use of smaller engines and reduced speeds. Such “slow steaming” has obvious limitations. The EEDI becomes stricter over time, and shipbuilders are now offering design improvements and energy savingtechnologies that promise substantial fuel economies. Several solutions, like waste heat recovery, hybridisation of propulsion, rotor sails, and air lubrication of the hull, can also be retrofitted on existing vessels.

The way a ship is operated also has a significant impact on fuel use. Maintenance of engine and hull, routing away from heavy weather, and better planning to avoid queuing in ports can contribute considerably to fuel savings. Such measures often pay for themselves but have been difficult to regulate. Nevertheless, the IMO has implemented systems to improve theoperation of all transport ships, such as the Carbon Intensity Index (CII), along with mandatory plans to enhance performance for every ship (SEEMP).

Despite these efforts, overall emissions from international shipping have

been increasing considerably over the last decade due to globalisation and growth in trade. Although the EEDI, other IMO regulations, and some voluntary schemes have reduced emissions from many ships, it is widely recognised that any pathway to net zero requires alternative zero-emission fuels. It is likewise understood that strong measures, such as a carbon price and stricter regulations, are necessary for such fuels to become viable for shipping.

The EU is leading the way

The EU has taken the lead in this regard. Since the beginning of 2024, it has included shipping in EU waters in its Emission Trading System (ETS), with a threeyear transition period. The legislation for the inclusion of maritime emissions in the EU ETS has been complemented by several implementing and delegated acts. The first report on emission data (2024) is to be submitted in September 2025. Other EU measures set a maximum limit on the greenhouse gas content of energy used by ships calling at European ports (FuelEU) and mandatory targets for shore-side electricity supply at maritime and inland waterway ports (Alternative Fuels Infrastructure Directive).

Ship finance and export credits

Shipping markets have historically been volatile, with ship financing traditionally being asset-based and long-term. The useful life of a ship is 20 years or more. A bad choice of technology can lead to the asset being stranded early. Today’s uncertainty around future regulations and availability of alternative fuel makes investment decisions for shipowners even more difficult and risky.

One recent study1 has found that shipping banks do not reflect this risk in their pricing of loans for individual ship transactions. Financial terms for new ships with high energy efficiency (good EEDI score) are similar to terms offered for new ships with relatively low scores. This is also the case for banks committed to the Poseidon Principles, a voluntary setup intended to provide a framework for integrating climate considerations into lending decisions. Still, the study finds that shipowners receiving a high score on climate commitments and plans get better financial terms in the market than those with a low score.

Officially supported export credits may have a role in changing that situation. The Shipbuilding Committee of the OECD, responsible for the Ship Sector Understanding (SSU) of the OECD Arrangement for Officially Supported Export Credits, has reactivated an expert group (IEG) to investigate ways for export credits to contribute to decarbonisation. The SSU was not part of the modernisation of the OECD Arrangement that came into effect last year, which accorded more lenient financing terms for an expanded list of low-emission sectors and transactions.

The role of ECAs going forward

Defining the standards for a low-emission ship is a first necessary step, and it is a considerable challenge in itself. Equally complicated and important to assess are which terms would have a measurable impact on shipowners’ decisions to invest in green technology. It should be noted that there is a limit to how generous new terms under the SSU can be. These new terms must not constitute an export subsidy, forbidden under the WTO.

The expert group began work this year and has held in-person meetings

bringing together experts and representatives from all the Participants to the SSU (signatory countries), with support from the secretariats of both the OECD Shipbuilding Committee and the export credit sector. Representatives from academia, ship classification societies, and other stakeholders have been invited to make presentations. They have engaged in constructive and open discussions, providing invaluable input.

We do not yet have an answer to the titular question of how ECAs can help decarbonise shipping. There has been substantial innovation and testing of new climate-friendly solutions in the industry. However, uncertainties about technologies and fuel availability remain, as do major questions about regulation and carbon pricing. Different ship types present distinct challenges. Tankers and cruise ships operate in completely different markets and there is specialisation among different shipbuilding nations. Any set of new common financing terms for

low-emission vessels must be agreed by all Participants, by consensus. The work of negotiating these new common terms is incredibly compelling but also difficult. We will need proactive collaboration, and perhaps some good luck, but remain hopeful for a successful outcome.

This article was first published in the Berne Union Yearbook 2024.

By Johan Mowinckel

Chairman of the

Informal Working

Group (IEG) under

the Shipbuilding

Committee, OECD,

and Director of

International

Relations at Eksfin.

Read more about: